Poor Things: An Analysis (with all the spoilers!)

Please do not read this if you haven’t seen Poor Things. This is an analysis meant for those who have already seen the film, now in theaters.

As an abstract painter, I’m keen on some well-known surrealists: Remedios Varo, Heironymus Bosch, to name a couple. But I’ve never been a fan of dreams for dream’s sake. The works of Dali and Matthew Barney fail to impress me for their reliance on aesthetic and lack of discernible intention apparent in successful composition. For me, these artists exemplify how composition and intention suffer for the sake of the bizarre and random, which elicit more shock and wonder than they lend to introspection and insight.

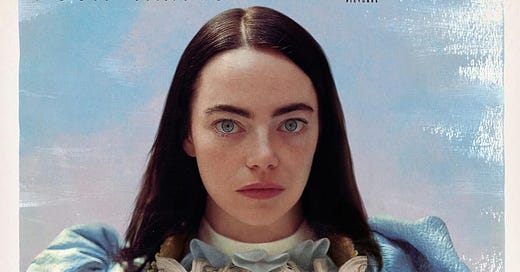

My hesitation going into Poor Things was that it would rely heavily on its lavish aesthetic. I was immediately delighted to see that this was not so. The sets are stunning enough for the audience to experience the wonders of this world through Bella’s (played by Emma Stone) eyes.

The fantastic environment also serves its purpose as a container for the characters, who, while whimsical, are refreshingly real by contrast. Accustomed to this world, they are astoundingly jaded in their wisdom. Thus, we experience Bella’s confusion. We ask ourselves, “How can anyone be jaded in such a beautiful world?” This question is also something we can ask ourselves about our own world, “How can I be so jaded in such a beautiful world?”

The writing is impeccable; evocative of Chekov and Mamet, harsh truths are made softer with poetic flair and upheld by strong performances not once lost in a visual cop-out. In fact, the most surreal moments of the film (aside from the fantastic elements in the story-telling) are depicted at the start of each new chapter; their purpose to remind us that we are watching a wonderful, modern fairy tale.

The film is introduced in black and white, reminiscent of The Wizard of Oz. Like Dorothy, Bella is a heroine on a journey of self-discovery. Initially isolated in routine, her mad scientist father, Godwin, or “God” as she calls him (she is, basically, a female version of Frankenstein’s monster. In fact, Mary Shelley’s birth name was Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin) keeps her within strict limitations. She is unaware of her captivity until she meets Duncan, who aims to free her. Duncan is the snake at her feet enticing her to eat from the tree of knowledge. Bella, an Eve archetype, heeds this “call” to experience the world, albeit under the influence of Duncan’s rakish character. Cinematically, the world becomes vibrant and colorful for Dorothy only after she enters Oz; Bella lands over the rainbow after her sexual awakening, which co-occurs with her entrance into the world at at large.

Through Bella’s experience with the world and the wisdom of those who inhabit it, Bella rapidly matures from an infant’s mentality to that of an adult’s. The advice she encounters on her journey is morose—at first, relayed by those whose capacity for joy is blunted by conditions of the modern world. Bella doesn’t understand humanity’s innate pessimism until her new acquaintance, Harry (played by Jerrod Carmichael), shows Bella the worst circumstances poverty can create.

In a later scene, after reconciling her feelings of what she witnessed, she provides insight for Harry, identifying him as, “a little boy who can’t bear the violence in the world,” to which he shamefully admits may be the unconscious root of his cynicism.

Swiney (played by Kathryn Hunter), Bella’s madame, reveals to her that she is caring for an infant; life itself is at stake, perpetuating the business and easing Bella’s criticism of the depravity and constraint she discovers in sex work. Here, Bella understands the complexity of human behavior; morality is sometimes leveraged in consideration of outcome. Catwoman, for example, will forgo moral impetus to achieve justice. Robinhood steals, but from the rich to provide for the poor.

A lot can be considered through the lens of allegory: kundalini awakening, the “call” of the heroine’s journey, biological adolescence (and its psychological implications), the biblical “fall” of man (Bella’s mansion is surrounded by a resplendent garden with fantastic creatures “God” created), women’s first and oldest profession: prostitution. Bella had everything, why would she ever want to leave home? Why would Eve ever seek something outside of Paradise?

Bella’s romantic relationship with Duncan is of particular significance. Though characterized, as mentioned before, as a bit of a snake, Duncan also doubles as an Adam-like figure. Bella influences Duncan, a self-proclaimed womanizer, to change his ways—albeit incidentally. He admits wanting to forgo his rakish lifestyle to marry her. Bella is conflicted because she is still engaged to Max (played by Ramy Youssef), Godwin’s student whom he has betrothed her to, indicating her plans to return home.

After gaining knowledge and insight through being a sex worker (yet another situation where men are, ultimately in control, albeit their sexual weakness being voluntarily exploited for money), Bella decides to leave the brothel and be monogamous with Duncan. Being conditioned by “polite society,” Duncan is irate and mortified after finding out Bella has been engaging in sex work. The double-standard here is obvious. It is acceptable for men to be womanizers, but unacceptable for Bella to embrace her sexuality and experience other partners, albeit in a different capacity.

Duncan’s behavior reveals that he does not support Bella because he loves her, but that he is angry he cannot control her. Bella sees his true nature: another man who wants to keep her captive. Although Bella’s lack of history contributes to her naiveté, it also facilitates her clarity. She is able to drop Duncan with conviction after his abusive outrage.

Duncan’s reaction is exemplary of men’s demonization of women since biblical times. In the mid-twentieth century, women were confined to asylums for hysteria into as recently as the 1990’s. In reality, behaviors deemed insane were reactions to the stress of having to fulfill certain roles as women at the hands of the men who drove them crazy. In this tale, however, it is Duncan who becomes institutionalized, and Bella is free to explore her newly embraced femininity.

Despite all of this, it is strangely easy to see why Duncan asserts that Bella is a demon. On a mundane level, the association between evil and women is obvious. Adam asserts that Eve persuaded him into sin as a cowardly attempt to relinquish accountability for his actions. Duncan does not accept responsibility for his behavior; it is Bella that drove him to madness. Understanding how this association came to be adopted into our Western rhetoric makes us aware of our own internalized misogyny.

The decision, too, for Bella to be created by a mad scientist similar to Frankenstein, makes us hesitate to identify her as human. Because she was created and not born, it’s appropriate to suggest she doesn’t have a soul according to some religious traditions (consider that certain religions, even now, are fundamentally against stem-cell research). However, by the end of the film, Bella attains wisdom—knowledge beyond intellect—suggesting that if she didn’t start out with a soul, she has indubiously developed one. This begs the philosophical question, like with Frankenstein’s monster and classic villain: Dexter—is a soul (or the concept of one) something we develop over time instead of being born with one?

Bella begins her journey without conditioning, a condition itself contributing to her amoral nature and perfect innocence. Of note is the part where her betrothed shows her a frog. Bella’s instinct is to kill it. This evokes the scene in Kill Bill 2 where the child accidentally (or not) stomps on the fish.

Though seemingly insignificant, this act alone sets the foundation for Bella’s learned empathy. Her heart breaks when she experiences powerlessness at the atrocities arising from the conditions of poverty—specifically, babies dying. As a result, she considers suicide. This echoes the conflict in her origin story; a mother who took her own and her unborn child’s life, powerless in saving herself and her child from the patriarchy (represented by her villainous husband, Alfie, played by Christopher Abbott). However, Bella decides to live. She has now matured beyond her previous incarnation and realizes the value in helping others.

What I love about the marketing for this film is the poster. The male characters pour out of Bella from her heart center, illustrative of a therapeutic modality: IFS—internal family systems. This aligns with my personal writing experience. I believe that all characters created by an author are unconscious personifications of different aspects of the self. While they can also be evocative of people we’ve met in life, fictional versions of them are interpretations of the author. We write how we see and understand others, not necessarily how they are. And how we see and experience others can tell us a great deal about ourselves. An open heart to others, as well as our ability to acknowledge their separateness from us (despite how we internalize and identify them) is intrinsic in growth.

Thus, I see Bella and Duncan as the feminine and masculine aspects we all harbor within ourselves. Their relationship is a physical incarnation, a microcosm, of universal forces. Duncan, one of multiple symbols of the patriarchy, is defeated by Bella with feminist protest. Until now, Bella has been swept off her feet by yang (male) energy: dancing, debauchery, sex, consumption, physical ardor and action, even thrilled by acts of violence.

Bella then walks off with Toinette, a friend and fellow sex worker, to join a Socialist meeting. It is here we understand that Bella has reached a new stage of development comparable to what Martha, a senior acquaintance (and cohort to Harry) she had made at sea in her travels, described: She is now paying more attention these days to what is between her ears, rather than her legs. Perhaps Martha is a personification of Bella’s innate wisdom—a crone existing within her potential as the possibility of a butterfly exists in every caterpillar.

After this, we are shown that Bella has sexual relations with Toinette, possibly suggesting Bella is finally embracing yin (feminine) energy. Her interest in socialism reveals her newfound consideration for morality and obligation to civilization. She has reached a stage past developmental narcissism. Her improved energetic balance allows her to identify that others exist outside herself, but within the humanity she too belongs.

I was delighted to find, after watching the film and embarking on the novel, a symbol that supports this symbolic analysis.

Upon befriending Godwin Archie McCandles (Max in the movie) discovers oddities in Godwin’s garden: two—interesting—rabbits. One previously all black, either male or female, the other previously all white, either male or female (it is not specified which color matched which sex). Godwin states that after surgically combining the two (such that one is half black, and half white and thus also half male and half female), they lost interest in procreation. In my estimate, this symbol is much too reflective Yin Yang to be coincidental; I speculate that this is setting a theme for the narrative. Both rabbits now are now in a Hermetic state, the ideal form of Adam Kadmon, the cosmic or divine “man” neither male nor female; or both.

A potential disappointment with the film is that it ends like most movies do: Happily—in a traditional sense. Bella gets married to whom she was always betrothed. She doesn’t actually break free of the constraints of custom. She doesn’t formally end up with her female lover. She doesn’t pave the way for socialist thought (a developed facet of her identity). Instead, she takes on Godwin (God’s) role after he passes. She adopts the work of the masculine creator archetype. She becomes king, not queen. This was my first interpretation of it.

Further contemplation allowed me to consider another perspective.

At the behest of Godwin, Bella must slough off her original existence to be born again, literally becoming her baby. This reflects resurrection myths (Jesus/Osiris) and also the virgin birth (impregnated by “God” who places the child’s brain in Bella’s body). She is Godwin’s female Jesus—and ultimately returns to Heaven. Throughout the film, Godwin asserts the value in repressing emotion for the sake of science. Bella, after resolving her emotional experience as a human being, knows she must continue her father’s legacy after his death. Thus, not only does she achieve balancing masculine and feminine energies within herself, she also achieves this on a cosmic or divine level.

Upon consideration of these aspects, it isn’t really an ending, but a beginning.

Instantly evocative of Tod Browning’s “Freaks,” I adored the depiction of this motley crew of characters lounging in the garden. One wonders what Bella knows about people and the world they’ve created to have subjected her ex-husband, Alfie, to this fate. Now that Bella is something more than human, we are to determine that Alfie was not capable of redemption, and therefore literally made to be the animal—the greedy goat—he always was.

Animal lovers such as myself may feel bad for the goat, though.